I'm Alexandra, a coach, therapist and DEI consultant. I run programmes to help live your truest life

hey there!

coaching for actors

categories

life design coach

therapy for high achievers

emdr

learn more

Popular posts

eMDR and attachment-informed eMDR. what are they?

What a life design coach is and how they can help

Why I Became A Coach for Actors

The "Toolkit to Happiness' is a simple neuroscience technique to re-wire your brain to experience more of whatever quality you wish for such as confidence, optimism etc.

download the freebie HERE

7 Benefits of Therapy for Actors

November 5, 2024

How can therapy benefit actors?

Acting feels like what you’re meant to be doing on this planet. It sets your soul ablaze and puts you in your happy place. When you act you feel like you’re in ‘flow’ state. You adore interpreting and creating characters and telling a story.

Well, most of the time.

At other times you feel down-hearted and dejected. You know you have more potential within you then you’re able to express. You feel stuck and helpless when you get the same old critique from teachers. The same old rejections from self-tape submissions.

That’s when therapy which is targeted and tailor-made for artists can help. By therapy I don’t mean CBT which mostly just tackles unhelpful thinking. Acting is holistic and we need a holistic therapy that works with body, emotions and mind.

I mean a relational embodied therapy like Gestalt therapy. Combined with a trauma-focussed therapy called EMDR which is good at shifting deeply held negative beliefs and processing painful emotions in the body.

As a therapist-coach for actors using Gestalt therapy and EMDR, I can support you in the process towards landing your dream acting job. I use the term actors throughout to keep it simple but I mean anyone of any gender/s who acts.

Here’s how therapy can benefit actors:

1. Greater Awareness of Your Emotions To Act More “Truthfully” and “Go Deeper”

According to Meisner, the aim of an artist is to express themselves as truthfully as possible. He says,

“ The truth of ourselves is the root of our acting”.He also says,

“Acting is behaving truthfully under imaginary circumstances.”Therapy gives you awareness of your true emotions, needs and motivations. Tis is a benefit of therapy for acting. You can then use them in your acting. By awareness I don’t just mean ‘knowing’ intellectually what you’re feeling or should be feeling. I mean really feeling all the nuanced range of feelings within your body.

Let’s face it, we don’t get taught how to identify and understand our emotions at school. Part of the therapy process is learning what we’re feeling.

The ABC of emotions

I remember when I first started having therapy many years ago. My therapist asked me what I was feeling as I was telling him about an argument with a boyfriend.

“Umm” I replied. I had no clue.

My therapist continued, “you must be angry about what he said”.

“Errr”, I replied. I just felt depressed. My heart area felt pushed down and heavy.

Then my therapist suggested I pretend my boyfriend at the time was in the therapy room. I imagined him sitting in a chair opposite me. I was invited to speak from the hip and say whatever stream of consciousness came to me as I looked at him.

I started off feeling depressed but within seconds I was raging at him like a bull in a cage. My therapist explained that depression can be understand as us pressing down an emotion. Rather than asking, am I depressed? I can ask, what emotions am I pushing down?

Just as we can push down anger, we can use anger to push down other feelings. Sometimes it feels easier to connect with anger than grief.

Connecting with deeper emotions in acting

Let’s look at an example from acting. You might be playing a role where the character is experiencing grief about having lost a child. Their grief is coming across to their scene partner (who is playing their husband) as rage. They’re shouting at their partner angrily in the scene you’re rehearsing.

I ask you to say out your lines to me. I am your substitute scene partner. I slow you down as you talk and ask you to observe what you notice in your body. You feel the burning rage in your face, throat and upper chest.

You can also feel an energy that feels like water flowing down from our heart and pooling in your stomach which feels heavy. It is mixed with a yearning feeling which you experience as an energy opening up in your heart area and flowing up to your throat and into your mouth. You come to recognise this as grief.

Knowing that you’re feeling anger as well as grief means you can express both when acting. Meisner says,

“it’s not about being bigger, it’s about going deeper”.This means drawing on the deeper feelings you have and expressing them when you act. Therapy can benefit your acting by helping you connect with deeper emotions.

2. A More Embodied Performance

Feedback I’ve received and heard many others receive is to be more embodied when I act. By this I understand allowing the script to affect not just my emotions and my thoughts but my body too.

Allowing my body to move and resonate with the words. When I’m not doing that my body is stiff and incongruent with my words or the emotions I’m feeling.

Western society in general puts a stronger emphasis on thinking than on feeling or sensing with our bodies. If we grew up in a sub-optimal environment then we also learned that our bodies aren’t safe places.

Emotions originate in the body. If we had painful feelings as a child that were not soothed by an attentive caregiver or were caused by caregiver, we do the most intelligent and creative thing we can at the time which is to disconnect from our bodies. We numb our bodies.

After a while we forget that we did that and how we did it is no longer in our awareness. We numb and disconnect from our bodies automaticaly. We’ve been doing it for so long that it just feels like that’s the way it is and there’s nothing we can do to change this.

So when our acting teacher tells us to connect with our body we feel stuck. We don’t know what to do. We try but we feel awkward and clunky.

So how can therapy help us to relate to our bodies differently?

It can support us to ‘just be’ with our bodies.

Using Gestalt therapy, I will often open the session by asking:

‘how are you right now and where are you feeling it in your body?”

It’s not unusual for a client to quickly say:

“I’m fine, how are you?” Or, “I’m ok, so I want to talk about…….”.I will slow you down and invite you to notice what’s happening in your body. Often you will then say,

‘actually, I’m feeling a bit anxious’.

We then explore that anxiety and I might ask you to sit with it and notice.

I tell you to imagine that you’re watching a wild animal, say a lion, at a distance on a safari trip. You’d most likely observe the animal attentively, being in the moment. You wouldn’t have any expectations.

You can do the same when you observe the anxiety in your body at the beginning of a rehearsal. You can answer the following types of questions:

- Where is it?

- Is it moving or static?

- Is it heavy or light?

- Is it hot or cold?

- Does it pulse?

- Does it vibrate?

- Is it ‘thick’ or ‘thin’?

- Where does it move to in your body?

As you sit and notice your mind will likely distract you. It might likely distract you a thousand times. Just as we are taught in mindfulness, this doesn’t matter. Simply bring your mind back to the sensation. Your mind might also tell you that you’re doing it wrong, that you’re no good at noticing.

This is untrue, you cannot be bad at noticing. Because whatever you notice, including the fact that you’re criticising yourself or drifting off, is worthy of noticing. Simply bring yourself back to your body.

In a therapy for acting session I might ask the following:

- Is there is an emotion that goes with the body sensation.

- Is there a colour that goes with the emotion or body sensation

- Is there an image that goes with the body sensation?

I could also ask you to have a talk with your body: “What do you want to say to it?”You might say: “I just see you as a means to an end.”

Or,

“I see you as a nuisance that I need to feed and hydrate’”

Or,

“I see you as a vehicle for attracting sexual and romantic attention”

Then we see what your body has to say in response. The more you gain awareness of your body in therapy, the more you connect with it and understand, the more you will do in your acting.Moving onto another benefit of therapy for acting…….

3. Trust Your Instincts More

I’ve lost track of the amount of times i’ve been told to trust my instincts more. I’ve heard my fellow trainees being told that a lot too so it’s common feedback. I’ve felt perplexed, like,‘What do they mean? “

“What are my instincts anyway?”

“How can I trust my instincts when I don’t know what they are?”

So how can therapy help us trust our acting instincts more?Cambridge Dictionary defines instincts as “the way people or animals naturally react or behave, without having to think or learn about it.”

I’ve really understood about instincts from observing my 8-week old baby. She cries when she’s hungry, cross or in distress. She farts when she needs to, poops when she needs to, falls asleep instantly when she needs to.

There is no screen between her instincts and her behaviour. She is totally transparent. Obviously we’re not striving to go around farting, pooping and burping when we need to.

However in terms of acting it helps if we know what are natural instincts are. We stifle our instincts due to the societal norms of appropriate behaviour. We also learn to stifle our instincts as a result of family norms, religious norms, and due to attachment trauma/abuse.

In therapy we explore how you block/suppress your instincts. It might be that shame gets in the way. Or that there is a trauma there that needs to be processed.

A case study

A case study which is an amalgamation of several clients is someone whom I will call Terry. They were struggling with a scene from a Roy Williams play where the character becomes irate. Terry could not let go and let rip.

They have a father with an erratic and angry temperament. As a child they learned that making themselves small meant they could avoid upsetting their father. They learned to stifle their angry reactions to their father. They learned to stifle their desire for closeness and warmth from their father to avoid the shame of being rejected by him.

Making themselves small and dimming down their need for connection was an intelligent and creative survival strategy as a child. It doesn’t serve them so well as the character they play.

So how do we resolve this?

In therapy I first helped them gain awareness. Terry made the connection between how they held back in their acting and how they held themselves back with their dad. They realised that whilst as a child the terror of his rage felt like life or death, they have survived.

As a child our nervous system is programmed to stay attached to our primary caregivers no matter what. If not we would literally die if we were abandoned by our caregiver.

Terry becomes aware that they are stifling rage towards their father. They also recognise that they’re safe now and that their father can’t retaliate. In the session I invite them to imagine speaking out their rage and other feelings towards their imaginary father.

They then channel this same anger towards their scene partner, imagining he is their father. They are more fully able to express this natural instinct of anger.

4. More RelationalI know I’ve seen great acting when I feel moved by what I’ve seen. Watching two actors connect and each be moved by the other moves me too. It’s also something I find challenging. I’ve received the feedback to try and really listen and be with my scene parner rather than anticipating my next line.

We might get told by our acting teacher to practice 360 degree listening. This is defined as focussing fully on the other person. It includes ‘listening’ in other ways. Taking in what the person is doing with their body and how we feel in our body as we listen to them.

All well and good to say this but what if we try and keep getting the same feedback?

As an acting therapist-coach I explore with you how you block connection and intimacy. This is often but not always, (neurodiversity might play a part) due to attachment trauma. We have learned that intimacy is unsafe.

Let’s go back to the example of Terry. They learned early on to suppress their yearning for connection from their father as he wasn’t able to connect with them. Instead he would be angry or cold. If he did connect it was briefly before breaking away.

Terry learned that wanting to connect with others was dangerous. They might get hurt like they did with their father. They also feel shame. This is experienced as a fear that if the other person gets close they will see what we’re really like and run a mile.

In therapy we do experiments between the two of us to give Terry a more healing experience of relating. This starts to re-wire their brain to believe connecting is mosty safe and that they can keep themself safe when connecting. It helps them to stay more present with their scene partner.

5.Trust the acting process moreI’ve been told i’m ‘trying too hard’ when i’m acting. I’ve been told to be more messy. I heard the same feedback being given to my fellow trainees. It seems to be a common critique.

But how do we try less hard in acting?

I remember feeling perplexed. Especially as I wasn’t even aware I was trying so hard. It’s even more difficult to change something that is out of awareness.

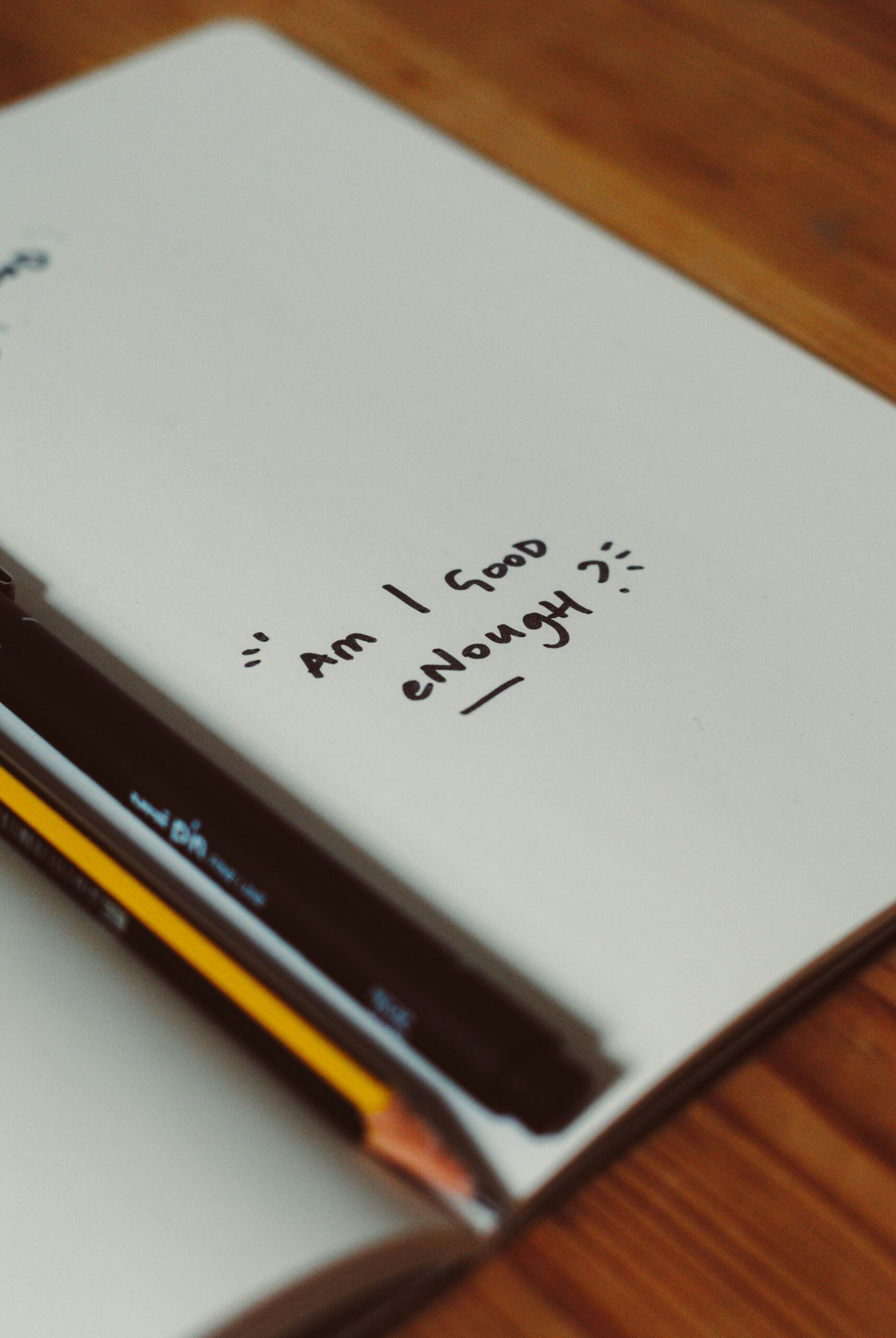

Trying too hard comes from believing deep down that we’re not good enough. Therefore we need to try extra hard just to be good enough.

Challenge the false belief we picked up as children

In therapy for acting we explore how you picked up this erroneous belief that you’re not good enough. You guessed it, it’s probably from childhood. This is where we pick up most of our beliefs which no longer serve us.

Some examples of negative beliefs are: I’m powerless, I’m unworthy, I’m unsafe, I don’t matter amonst others. We don’t walk around thinking them. They’re there in the background, out of awareness and they influence how we feel, think and behave.

Here’e an example of how I worked with Sammi to shift their ‘not good enough’ belief. First we explored and established that she had picked up this belief from being around her mother. Mother would get depressed and withdraw a lot. Sammi did what all children do and made this behaviour about her. This is an instinctual survival tactic to have a semblance of control.

The out of awareness thinking is,

‘if I’m not good enough then all I need to do is change my behaviour. Then I will be better and mum will be less depressed”

Of course this doesn’t work because mum continues to be depressed. But Sammi keeps hanging on to the notion it’s her fault and she’s the one that isn’t good enough. If she accepted the truth, which is that mum’s parenting is ‘not good enough’, that would mean she is scarily on her own.

For a child’s nervous system, being on their own feels like they’re literally about to die. Far safer therefore to put the fault on themselves rather than the parent.

Experiment with behaving as if you are ‘good enough’

So once Sammi became aware of what she was doing did she change? No. She also needed to experiment with behaving differently and re-wiring her brain.

I got her to experiment with ‘acting’ good enough in the room with me. I asked her to speak one of her monologues as if she genuinely believed she was good enough.

I asked her:

- How would you look at me?

- How would you speak to me?

- What is your tone of voice?

- How do you hold your body?

- What do you fear would happen if you said your lines as if you were good enough, really good enough?

Sammi noticed she was a lot more relaxed acting in this way. However when anticipating doing the same in rehearsal she felt scared that she wouldn’t be able to convey deep emotions is she wasn’t ‘trying hard’.

We explored the deeper fear. This was that her tutor would write her off as a terrible actress if she didn’t express deep emotions. I challenged her, “Is this really likely?” “No”, she said, ‘they would just think it was a one-off bad performance’

This gave Sammi the courage to start believing she was acting ‘good enough’ and to let go of trying so hard. She realised that rather coming across as unemotional she came across as more ‘real’ and more engaging.

6. Stop ‘schmacting” (over-the-top- acting)

As an acting coach-therapist I can help you soften the inner critic. The inner critic causes us to do ‘schmacting’.

It says,‘that was shit’

or,

‘you were really stiff just then’

or,

‘you’ll never be an actress, you’re hopeless, give it up now’.

We’re so desperate to shut it down that we over compensate and act in a over the top way.

Often if we have a criticial part we also ‘project’ that part onto others. Projecting means we imagine they have the same critical part as we do and that they’re judging us the way we judge ourselves.

Dana who came to see me explained how it made her start ‘over-acting’ also known as ‘schmacting’ to avoid being criticised by her teachers.

Befriend the critical voice

I invited her to put her critical part in a chair opposite her in the therapy room. I asked her to tell me about it. I asked her:

- How old is the critical voice?

- What does it look like?

- How long has it been around?

- How did it develop?

She then sat in the critical voice’s chair and answered as them. They had developed in childhood to pre-empt their mother’s criticism.

This was what we call in Gestalt therapy a creative adjustment. If Dana criticised her appearance before her mother did then it lessened the hurt she felt. The critical voice was trying to soften the blow of her mother’s criticisms.

I explored with Dana what her critical voice feared most. It feared that she’d be crushed. She recognised however that she can handle feeling crushed.

She’d felt crushed many times by feedback from acting tutors. And she’d survived. So she didn’t need this part to protect her. She could experiment with something different.

I invite her to experiment with saying her lines to me and this time imagining I’m seeing everything that is good about her and her performance.

- How does that feel?

- How does that change how she acts?

She notices that the need to over-act reduces. She can relax and be herself more. As Meisner says,

“Your acting will not be good until it is only yours. That’s true of music, acting, anything creative. You work until finally nobody is acting like you.”

7. Self-regulation so you are present in the role even after a bad day

Akbar came to see me because he wanted to perform more consistently. He noticed that if he’d had a bad day at work or an argument with his boyfriend, his performance suffered.

It sounded to me like he needed to find ways to regulate his emotions and nervous system better.

We looked at ways he can support himself with deep breathing and specific exercises that get him into his body and out of his mind.

EMDR to contain your thoughts

We also used an EMDR technique to imagine a container with a lock. As he tapped bi-laterally on his thighs with his hands, he imagined his individual worries and thoughts flying into a box. He then locked the box and put it in a safe space. He told the worries and thoughts he would take them out again when it was appropriate. He kept tapping till he felt a sense of peace.

I used another EMDR resourcing technique with him. This was to imagine a safe space. It could be a real place or an imaginary place. I suggested a place in nature as a good place. We want the image to be neutral. It’s not a good idea to imagine a safe space with others in if we’re then going to remember an argument we had with them.

The safe place

First Akbar imagined the scenery, the smells, the sounds and the sensations of the safe place. Then I invited him to notice what his body felt like in this safe place. He then did some bi-lateral tapping to enhance this feeling whilst telling himself he was safe. He tried these techniques out before his rehearsals and acting classes and felt more consistently calm.

I’ve covered here some of the benefits of therapy for actors and actresses. Therapy can also help with other issues actors face such as: sabotaging behaviour, disassociating parts, stage fright, addictions, low mood/depression and fear of exposure, amongst others. I’ve written an article about working with audition rejection which you can read here.

FREE TOOLKIT TO INCREASED HAPPINESS

Rewire your brain with this simple neuroscience proven technique to instantly feel more: (insert word of your choice) bold; calm; optimistic; organised;.. etc.

Comments will load here